Gilroy McMahon Architects: Croke Park Stadium, Dublin

Text © Shane O’Toole. GAA match photo © Brendan Moran/Sportsfile. Photo of Ireland-England rugby international © PA Photos. Other photos © John Searle, courtesy Gilroy McMahon Architects. Drawings © Gilroy McMahon Architects. Fuller version of the piece first published in The Sunday Times, September 8, 2002, as “Cathedral of dreams: the new Croke Park is a magnificent monument fit for the faithful”.

If sport is, as some contend, a form of religious devotion, then Croke Park, rising above the capital, is the gleaming cathedral of the new Ireland. Unveiled for this year’s championships, the GAA’s (Gaelic Athletic Association) temple of dreams – a pantheon of passion for a sports-mad people – is set to become the largest stadium north of the Alps. [With a capacity of 82,300 since the new Hill 16 – taking the form of a breaking wave – was enlarged in 2005, only four venues in Europe are bigger: Barcelona’s Camp Nou, Madrid’s Santiago Bernabeu, Milan’s Stadio San Siro and London’s Wembley.]

In their search for superlatives during recent weeks, some fans and commentators have taken to calling the new headquarters of the amateur sporting organisation – which is 12 storeys high, with sides measuring 220m 160m and 200m – a Celtic coliseum. They may be closer to the mark than they realise. The redevelopment’s genesis lies in a menacing brawl that brought us as close as we have ever been to suffering our own Ibrox, Heysel or Hillsborough.

The story goes back almost 20 years, to the 1983 All-Ireland football final – a bad-tempered contest between Galway and Dublin, played in foul weather. Five players were sent off. The mood in the crowd grew ugly. Soaked by incessant rain, fans on the greasy Hill 16 – a grassy, mounded terrace at the Railway End of Croke Park, formed from the rubble of destruction in O’Connell Street in 1916 – broke into the adjacent stand and forced some spectators out of their seats, injuring a steward in the commotion.

The warning was heeded. The stadium’s capacity was immediately reduced to fewer than 70,000, with the precise number agreed on an event-by-event basis with the Gardaí and the fire department. The huge terrace under the Cusack stand became seated and by the end of the decade Hill 16 had been rebuilt. Meanwhile, American stadium designers HOK Sport and the Lobb Partnership from Britain (who merged in 1999) were commissioned to advise on redeveloping the stadium. They prepared a development control plan, which involved pivoting the pitch by eight degrees around the corner flag between Hill 16 and the Cusack stand. The idea was that the pitch and the new Canal End stand should track the line of the railway and canal passing immediately to the south of the ground.

While this facilitated the development of a rational structural support system for the stands, it was immediately obvious, due to the restricted dimensions of the GAA’s landholding, that a bowl stadium could never be achieved. The finished scheme would be horseshoe-shaped. In fact, the development control plan proposed the removal of Hill 16, except for a few token rows.

Following a competition in 1989, the GAA appointed Des McMahon of Gilroy McMahon to design the new stadium. For McMahon, who had played centre half-back for Tyrone at junior, minor and senior levels, it was not just the greatest project of his career – he was coming home to the game he had abandoned in the mid-1960s, when he took up studying architecture, because he “couldn’t train and do all-nighters in the studio as well. I don’t think the grin came off my face for a fortnight,” he recalls. “When I got up in the morning, there it was again.”

The GAA is not just a game, but a culture. McMahon’s father, Jim, a schoolteacher from Roscavey, played a significant role in establishing the GAA in Tyrone in the 1930s and 1940s and played a Dublin league game in Croke Park for Erin’s Hope, the team of St Patrick’s teacher-training college, on Bloody Sunday in November 1920 when, during the second match that day, British forces invaded the pitch and opened up on the crowd – killing 13, including two players – in reprisal for the assassination in Dublin earlier that morning of the 14-strong “Cairo Gang” of intelligence officers.

McMahon says he often thought of his father, who died in 1976, while he was designing the stadium. One of the touches of which he is most proud, is the integration of the Árd Comhairle facilities into the premium level of the Hogan stand, named for one of the players killed on Bloody Sunday. “People like my father could never have afforded a premium seat in Croke Park,” he says. “The cost of one over ten years is like having a small mortgage. But once a year, the likes of my father can now rub shoulders with the Taoiseach in the VIP area – the cutting edge of Irish society and the grassroots of the GAA meeting, cheek to jowl.”

McMahon’s research – into logistics, crowd movement, comfort, safety and marketing – was intensive, the challenge immense. “We were making a major landmark in the city, a statement about the GAA and its place in Irish society at the end of the 20th century,” he says. “A landmark that would endure for at least a century in a city that still hadn’t forgiven Liberty Hall for its height or Sam Stephenson for the Wood Quay bunkers.”

The design team traveled the world, analysing the state of the art in stadium design. In Italy, they inspected the World Cup venues at Turin, Genoa, Rome and Bari. They saw the best in Spain and Germany. In Britain, Twickenham, Old Trafford and Highbury were visited. They went to Australia and North America – to Boston, Buffalo, New Jersey, Baltimore, Washington, North Carolina, Florida, Kansas and Colorado.

“Stadiums break down into two generic types,” says McMahon. “There is a distinct divide between the European and North American approaches. European stadiums have the better visual impact – the engineering is much more elegant.” Their form is generated by decisions about crowd capacity and architectural engineering – how to tier the stands and design the roof. They are funded by the taxpayer and often owned by the city, not the clubs. “That would be anathema here,” says McMahon. “It was never going to happen. So we used the more inclusive American approach rather than the leaner, more design-led European model.”

American stadiums are funded privately. The fans spend more time inside the venues, because the games go on for longer. Spectators are segregated into different categories, each supported by its own level of social activities which generate funds to offset building costs. They are often ugly and brash, excessively scaled and dressed up in a vacuous postmodern idiom that tends to give them the appearance of tacky commercial banks in search of an identity. Dublin demanded better.

At first glance, it may be hard to see the revolution that Croke Park represents and why it is having such an impact on other stadium developments, such as Arsenal’s proposed new 60,000-seater home in north London. But it is the first stadium in Europe to have been built on the American principle of horizontal, rather then vertical, segregation. It is this radical departure that makes the interior of the stadium feel like a grand hotel, with lobbies and concourses on several levels stretching for more than half a kilometre – all the way from one end of the Cusack stand to the opposite end of the Hogan stand. Walking the horseshoe – which can cater for 1,200 meals plus a huge variety of snacks served at bars and concession outlets – from one end to the other, it feels like one big room.

Spatially more generous than the American model, Croke Park is setting the agenda for the next generation of stadiums. It is light years away from the old, familiar “two-up, two-down” European model – the stadium as a terrace of houses, each section organised around its own staircase. It is built around the concept that people gather hours before a GAA match to socialize and to reminisce – to be part of a community.

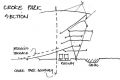

The form of Croke Park emerged from its cross-section. Market research defined the mix of spectators – the number of people to be accommodated in each section and the number of corporate boxes. “Boxes here are separated from the premium level, which has never been done before,” says McMahon. “As a result, the premium level has a gregarious character that is not possible in the cramped corridor arrangements of American stadiums.” McMahon went out on the road with GAA President Peter Quinn and Director General Liam Mulvihill to sell the scheme to the grassroots, who funded the development with help from the government. They covered the 32 counties in a series of county meetings, addressing three members from every club in the country.

The key to the design of Croke Park lay in solving the problems associated with the Canal End stand, 70% of which is located in airspace, overhanging the freight railway and canal. Conventional stadium design supports tiers of seating on a series of “H” frames – posts and beams – with each tier progressively higher and further away from the pitch. McMahon singles out his engineers, Horgan Lynch, for their ingenious, “tuning fork” structural solution, which picks up the packed central levels of accommodation, stacking them vertically, without any set back, at a comfortable distance from play. “I still think the solution to a local problem and the larger issue of making people feel good is ingenious, fabulous,” he says.

The “stiletto heel” structure lands outside the original stadium boundary, between the railway and canal, accommodating almost 14,000 seats in air space outside the curtilage of the site, over the railway and canal bank. This was the key to saving Hill 16 while increasing the size of the pitch, which is seven metres longer and three metres wider than before. The development of the leaning structural frame, unique to Croke Park, produced a bonus: the tiers pitch out towards the field of play, ensuring that a large percentage of spectators on four tiers enjoy the same focal proximity to the action, creating a rare communal intimacy. Even better, the concrete structure flows easily into the roof truss, in an organic and natural way, like the branches of a tree.

More than any other part of the stadium, the roof – or more precisely, the lack of cover it affords from rain – has come in for criticism. Although a pressure bulge develops over the stadium, reducing rainfall by 30%, complaints forced a rethink as the development progressed. It is the one part of the finished design that appears gauche: the earlier phases of the cantilever roof extend 34m, while the last phase – over the Hogan stand – extends 48m. The overall effect, despite the subtleties of the design which responds to orientation by varying the amount of glazing in each canopy, looks clumsy.

“In retrospect, we wouldn’t make that decision again,” McMahon admits. Back in 1992, the GAA believed they couldn’t afford the extra £2m which would have been added to the construction cost for every extra metre of cantilever over and above the initial 34m. Now they make that much whenever there’s a major championship match.

The huge extra cost was a result of the horseshoe shape and phasing, as the roof of each stand had to be independently stable. The optimum shape for a column-free stadium roof providing full cover is circular or oval, where the front edge of the cantilevered roof can be designed as a compression ring that prevents it sagging. The biggest problem facing a horseshoe cantilever is bending from uplift, however, caused by wind rushing in under the canopy. The longer the cantilever, the greater the strain, and full rain cover would have required the stand to project well beyond the touch line, leaving only the central 40% of the pitch uncovered. Exposing the steel structure above the roof produces the turbulence necessary to prevent uplift of the roof.

The pitch is a sand-soil mix – as pioneered at Anfield, Villa Park, Highbury and Old Trafford – that anchors a blend of grasses and 100 million linear metres of polypropylene string, with a forced-air vacuum ventilation system of pipes beneath the surface – installed and maintained by Hewitt Sportsturf of Leicester – that can be used to vacuum-drain the grass after heavy rain or, conversely, distribute blown warm air to clear frost or snow.

Twelve years is a long time to keep your focus. McMahon was in his forties when he set out on this odyssey. He is now 61. His partner, Deirdre Lennon, an architect and formerly assistant project manager to Roland Paolotti on London Underground’s Jubilee Line, helped him oversee the recent phases. What pleases them most is how the monumental, 12-storey stadium responds to the three scales it must address, as it is seen from across half the city, in the neighbourhood and up close. “The three great classical virtues of architecture are base, middle and top,” he says. The crown of interlocking elements is cloud-grey, like the sky. The middle is slate blue, like the roofs of its neighbours. And the base presents a different face to each context – whether it is the front on residential Jones’s Road, the canal or the back, with its turnstiles leading to the Cusack stand.

It is a magnificent monument, one with a human face. They have built it and we will come.

Croke Park http://www.crokepark.ie

Gilroy McMahon Architects http://www.gilroymcmahon.com