Scott, Michael (1905-1989)

Michael Scott (1905-1988) is considered the most important architect of the twentieth century in Ireland. Apart from Busáras, his most important buildings include his own home Geragh at Sandycove and Donnybrook Bus Garage. He was born in Drogheda, County Louth in 1905. His family originated in County Kerry and he was educated at Belvedere College, Dublin. There he first demonstrated his skills at painting and acting. Initially he wanted to pursue a career as a painter but his father pointed out that it might make more financial sense to become an architect. Later in life Scott said about his childhood:

I think he was right because I’ve always been interested in shaping materials since the day, when aged six, to my delight, I caught a glimpse beneath my teacher’s skirts of a well formed wooden leg.

Like most other Irish architects of his day Michael Scott did not study architecture at the Schools of Architecture, but was articled as an apprentice for the sum of £375 per annum to the Dublin firm of Jones and Kelly. There, between 1923 and 1926, he studied under Alfred E. Jones.

Jones and Kelly were at this time a conservative practice. They were responsible for housing estates at Mount Merrion, Dublin based on the garden city ideal and for the last major public classical building to be built in Ireland – Cork City Hall, finished in 1935, on which Scott worked for a time. Scott later claimed that it was not until he left Jones and Kelly that he became aware of the trends of modern architecture while in fact the firm had a great architectural library with many books on current European architecture and design of the period.

During his apprenticeship, Scott joined Sarah Allgood’s (1883-1950) School of Acting at the Abbey Theatre and appeared in many plays there until 1927, including the first productions of Sean O’Casey’s (1884-1964) Juno and the Paycock and The Plough and The Stars. During the period 1923-1926, he was also studying art at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art in the evenings, alongside such people as Maurice MacGonigal (1900-1979) and Nano Reid (1905-1981), and under the tutelage of Sean Keating (1889-1978), who was Professor of Painting. These relationships were to prove important, as Scott was to commission work from these artists in later years. In 1926 he was elected head of the Students Union and organised an Arts Week with lectures, plays and exhibitions. He took the lead role in a play during this Arts Week, King Argimenes and the Unknown Warrior – the set was designed by Maurice MacGonigal. Scott’s total immersion in the arts and Dublin artistic society through his acting and painting was to provide important contacts in future years and be the source of valuable commissions for his firm.

After leaving Jones and Kelly, he worked for a time in the offices of Charles J. Dunlop as chief assistant architect followed by a year in the Office of Public Works Architects’ Department designing headstones. He was responsible for the conversion of the Gate Theatre, Dublin at this time. This was for Hilton Edwards (1903-1982), who was to remain a life-long friend, and involved the conversion of the Ballroom and the Supper Rooms above, into an auditorium and the construction of a stage in an adjoining room. After Edward’s death, Scott inherited his share holding in the theatre.

He remained at the Office of Public Works until 1927 when he was asked by Sean O’Casey to tour the United States of America with the Abbey Players for six months. That same morning he received a letter from the secretary of St Ultan’s Children’s Hospital in Charlemont Street, Dublin. Madeleine ffrench-Mullen (1880-1944) asked him to design a new wing for the hospital. After deliberation, it was decided that he should go on the tour with the Abbey while observing the latest trends in hospital design in the United States, and then return with ideas for St Ultan’s. While he was there, Scott contemplated taking a job as an architect, taking up painting or acting full time. He was staying with his friend, the artist Patrick Tuohy (1884-1930) and was playing the lead role of Jack Clitheroe in the Broadway production of The Plough and the Stars. In the event he returned home to practice architecture from his father’s front room. The new St Ultan’s wing was opened in 1929 and was to be the first of many hospital commissions.

After an approach from Sean O’Casey and due to financial problems, Scott took up acting once again in 1929. This was the lead role of The New Gossoon by the Abbey Dramatist George Shiels (1886-1949) at the Apollo Theatre in London. Scott assumed the pseudonym of Wolfe Curran in an attempt to keep his acting career a secret from other architects. He was quite successful and acquired good reviews but the subsequent attention (from the Daily Express which exposed him as Michael Scott, an Irish architect) caused him to retire after three weeks. He never acted professionally again. The theatre was owned by J.B. Fegan who also owned another theatre in Oxford that needed renovation. Scott was interested in the job and took the part in the play on the understanding that he could have a drawing board in his dressing room.

In 1931 he joined forces with Norman D. Good to form Scott and Good, and they opened an office at 36 South Frederick Street, Dublin. Good was a successful businessman and a good draughtsman while Scott was responsible for most of the design work. The Irish Hospitals Committee had started the Hospital’s Sweepstakes, a lottery in order to raise funds to fund the modernisation of the State’s hospitals and as a result many hospitals were being constructed or extended. The Irish Government decided that a modern image was required for these hospitals and the Minister for Local Government and Public Health, Sean T. O’Kelly (1882-1966) compared Ireland to Finland, and suggested the work of Alvar Aalto (1898-1976) as examples. In a lecture to the Architectural Association of Ireland in 1933, O’Kelly stated: We too in this country have room for men who will give to our peculiar problems the intense study they require, and help us build in a manner that will reflect credit on our country and generation.

There was a keen interest in architecture from the Government ministers of the new state and they were often present at meetings of the AAI. The Hospital Sweepstakes building (Robinson Keefe, 1937) was itself a work of modern architecture with a long low front elevation with a glazed tower at one end. All of the new hospitals built in the 1930s were modern in style and the main beneficiaries of work were Vincent Kelly who was on the Sweepstakes Committee, T.J. Cullen (1880-1947), and Scott and Good, who rapidly gained reputations for designing hospitals and received one commission after another.

Scott and Good’s hospital at Tullamore (1934-37), although faced with traditional limestone masonry, has a very strong horizontal linearity and glazed stairwell that show a Dutch Modernist influence in the massing and the use of a round bay in the centre of the main block. The massing is reminiscent of work by Willem Dudok (1884-1974) at his school at Hilversum while the round bay is suggestive of the housing of J.P Oud (1890-1963) at Hoek van Holland (1924-27) whose work Scott saw and admired on a visit to Holland in the early 1930s. The main block is strongly symmetrical, showing the traditional training of the architects, but the building is entered from one end allowing an asymmetrical end elevation in the International Style. The ground floor elevations are dominated by a range of round headed windows. This unconventional use of materials with the massing treatment of International Modernism shows Scott’s interest in the use of materials for decorative purposes.

In 1935 they designed Portlaoise General Hospital. This building unlike its predecessor, does away with traditional massing and materials. It is a flat roofed, white plastered horizontal structure that ultimately fails to be as interesting as its mixed breed ancestor. Again strongly symmetrical, the entrance is flanked by two stripped down columns supporting protruding masses. The rear elevation is much more successful with a strong horizontal linearity. Both hospitals have symmetrical plans, with Portlaoise being designed with the operating theatre in the centre of a ‘H’ plan. After a while Scott consciously tried to avoid taking on any more hospital jobs in order not to become labelled as a hospital architect. He claimed to be so successful at this that he was not asked to design one afterwards.

In 1935 a competition was held to design new offices for the Department of Industry and Commerce in Kildare Street, Dublin. Scott and Good submitted their entry only to be unplaced. The journalist and architect John O’Gorman (born 1908), writing under the pseudonym Wisbech in The Irish Builder and Engineer, wrote of the results that ‘he found it a complete mystery why the scheme submitted by Michael Scott and Norman D. Good was neither placed nor commended’ adding: [it] was encouraging, however, to note several schemes from young (and in some cases not yet qualified) architects which to my mind showed a sounder grasp of the realities of architectural design than those which came from men who have for years acted as councillors, examiners and assessors.

O’Gorman went on to write that the elevations of the Scott and Good entry were ‘outstanding’ reminding him that ‘this is the year nineteen-thirty-six and that Ireland is not entirely cut off from cultural movements on the continent’. A major fault with the design according to Wisbech seems to have been its height, in that the cubic office capacity other entrants got into four storeys, Scott and Good got into seven. He also mentions that ‘there was evidently no cheese-paring’ on grounds of cost – an early indication of Scott’s refusal to compromise his work. It seems that Scott and Good placed their design back from the building line on the street, creating a small plaza in front, as Wisbech refers to the footpath being carried over the site, adding dignity to the design. The winner was Basil Boyd Barrett, who was also a student at Jones and Kelly at the same time as Scott.

Scott and Good were also responsible in association with the London architect Leslie Norton between 1934 and 1935 for some flamboyant exercises in Art Deco Cinemas in Dublin – the Theatre Royal, College Street and the smaller Regal Cinema next door to it. Scott, although not responsible for the interior design or exterior form of the building, was responsible for the commissioning of artists to produce work for the building. Scott commissioned the sculptor Laurence Campbell to produce a triptych relief panel of ‘Mother Éire’ for the front of the Theatre Royal. Scott was to use the work of Campbell often to decorate his buildings in the future.

Between 1937 and 1938, Scott was the President of the AAI and was instrumental in bringing Walter Gropius (1883-1969) to Dublin where he gave a lecture at the Engineers Hall in Molesworth Street on 10 November 1936. The lecture was entitled ‘The International Trend of Modern Architecture’ and was heavily reported in architectural journals and other publications by John O’Gorman who was Ireland’s great exponent of the International Modern style. He performed much the same role for The Irish Builder and Engineer as P. Morton Shand did for the Architectural Review in London. O’Gorman was also an outspoken critic of the older generation of Irish architects, who persisted in designing and educating in outmoded styles, particularly Rudolph Maximillian Butler (1872-1943), the Professor of Architecture at UCD. O’Gorman started his review with a tirade against them:

The large and representative audience which assembled to hear the eminent German architect, Dr Walter Gropius, on ‘The International Trend of Modern Architecture’ may be regarded as an encouraging omen for the future of architecture in Ireland, consisting as it did of so many of those successful architects whose life-work has been a negation of everything that Gropius stands for, sitting side-by-side with those of a younger generation who are faced with the thankless case of undoing the harm caused by their elders.

This lecture was based on Gropius’ recently published book The New Architecture and the Bauhaus (1935) and the conclusion of the address was almost word for word the final page of the book. Scott later stated in an interview with Build magazine on the importance of the Bauhaus and Walter Gropius to his architectural development that: The Bauhaus was a remarkable event in the history of architecture. It had a dramatic event on the whole creative world. When I became aware of it, I really began to understand what I was doing.

Scott’s position as President of the AAI was the result of the influence wielded by his friend Vincent Kelly, influence that was to result in Scott receiving the commission for the New York World Fair of 1939. Shortly before Gropius’ visit, Vincent Kelly was responsible for a book review of Nikolaus Pevsner’s Pioneers of Modern Design (1936) in the magazine Ireland Today. This is an early indication of the way that Scott and a few friends would come to dominate the arts and patronage after the Second World War. According to Ciaran MacGonigal, Scott had a ‘high regard for power’, political or otherwise and would always try to cultivate those with it.

During this period, he was also responsible for bringing other architects, designers and artists to speak to the AAI, including Erich Mendelssohn (1887-1953) whose lecture was titled ‘Rebuilding the World’, in which he traced the basic reasons for the natural development of modern architecture. Other speakers included the typographer Eric Gill (1882-1940), the artist Sean Keating, Frank Yerbury from the Architectural Association in London, R.S. Wilshere (who was the architect to the Belfast Corporation Education Committee and heavily influenced by Dudok) and Lennox Robinson (1886-1958), a dramatist and producer with the Abbey Theatre.

In 1938 Scott left his partner Norman Good to set up his own practice: Michael Scott Architect. That same year he also designed his house Geragh, at Sandycove, County Dublin. He had bought the site by the martello tower some years before, and originally intended it as a site to build a home for his father who was a keen fisherman. He refused it so Scott built a house for himself. The house was named after the valley in County Kerry where his father was born. Scott never had much money, but he had, in the parlance of the day “married well” in 1933 and his wife Patricia had inherited a small amount of money. This was around £5-6000 and was used to buy the site and build the house. He became so enthusiastic about the site that he claimed to have designed the house in one day.

This was because the eccentric old lady, Mrs Chisholm Cameron from whom he bought the site had sold it on the condition that construction should start within three years. Due to other commitments Scott forgot about this, but then received a letter in the post reminding him of this clause, and so a design had to be rushed out, hence the claim above. The house is sited in an old quarry next to the Forty Foot bathing place and martello tower and seems to rise out of the rock. A public pathway winds its way around the seaward side of the site and so for privacy and protection from the prevailing wind, the building faces towards Dun Laoghaire rather than out to sea. It was one of the first houses built in this country using mass concrete throughout. The concrete is rendered externally and painted white. Using the maritime imagery of the International style, the house is made up of a series of decks, railings and portholes – indeed one end resembles the stern of an ocean liner with a descending series of circular bays and crescent balconies – a motif which also reflects the nearby martello tower and naval defences at the Forty Foot.

The tower is associated with James Joyce (1882-1941) through the opening passage of Ulysses and now contains the Joyce Museum. This curved bay feature was much used by Scott in this period – being used in his house for Arthur Shields (1934) where the living room is projected out with a curved bay and also at the hospital at Tullamore where a series of curved bays are placed above one another. The flat roof and balconies all command great views over Dublin bay. Original to the aesthetic of its day, it was originally sited on stilts, but over the years the spaces underneath were filled as the family’s needs expanded, but apart from that it remains intact. The house is basically a shallow v-plan embracing the garden with one end rectangular and the other round nosed.

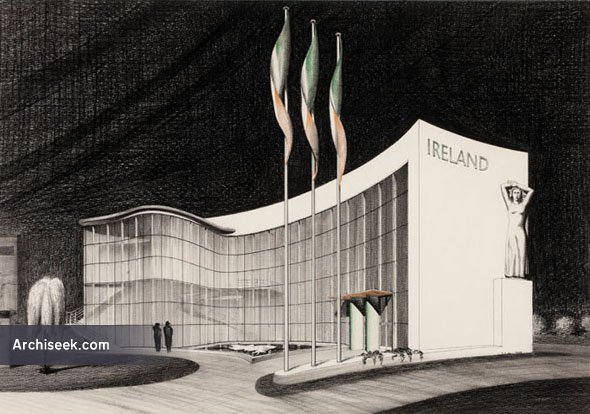

This purer form of modernism was to be carried through to Scott’s most important pre-war commission – the Irish Pavilion for the New York World Fair. This was completed before his final examinations. Scott always had a distrust of academic qualifications and had to be persuaded to sit the RIAI special final examinations to become an MRIAI. Ironically the dedication of the fair was ‘A New World of Tomorrow’ with a guiding theme of ‘a fuller, happy existence for the average man’. A great deal of politics was played out behind the scenes with Ireland being first offered a site with the rest of the British Empire. Pressure was applied by the British who felt that political interests would be best served by the Empire exhibiting as a block rather than scattered over the site at Flushing, New York. After resisting this pressure and more, Ireland eventually acquired one of the best sites on the grounds, thanks to the European Commissioner for the fair, John Hartigan, who was in constant contact with the Taoiseach, Eamon de Valera (1882-1975), informing him of the British position. This pressure and political manoeuvring was reflected in the commissioning of Scott, as both the Architecture Graduate’s Association, and the RIAI favoured an architectural competition to select the design for the building. The RIAI wished to send a representative to the Government to promote this idea, and Vincent Kelly proposed Scott. Other members wanted Scott to be accompanied by a representative of the AGA, but this was rejected after pressure from Vincent Kelly. So Scott went alone to the Department of Industry and Commerce in April 1938. Scott was not formally appointed until 10 June 1938 but travelled to New York the next day with a full set of drawings and a model. It seems likely that Kelly and Scott orchestrated Scott’s trip to the Government on his own so that Scott would get the commission – F.H Boland who was Assistant Secretary to the Department was a friend of Scott’s and married to the artist Frances Kelly whose work Scott used at Tullamore. Vincent Kelly always tried to promote Scott – at one stage he was encouraging him to be the president of the RIAI.

This was the first appearance of Ireland as an independent country at an international trade fair and the Government of the day was determined that the building must have a modern and high quality yet recognisably Irish character. In an interview with Nicholas Sheaff, Scott said ‘that it was essential to build something which would make a direct appeal to the 25 million Irish Americans’.

Scott produced a shamrock shaped building constructed in steel, concrete and glass. He had played with traditional Irish vernacular architectural styles like beehive huts and thatched buildings until:

The curving organic outline of the building gave it a cosy feel and made it very popular. Indeed it was known as the Shamrock Building by the tour buses that toured the fair. Scott though felt that its success was ‘a phoney because he had to use a theme to meet the brief’. He felt that a national style or character was in the use of materials, its function and climate not the external shape of the building. In later years as the use of the shamrock in Irish design became clichéd, he was to claim that the plan was forced upon him by a member of the Government. This use of curtain glazing is a fore-runner of the bus station concourse at Busáras.

One of Scott’s driving philosophies was the integration of art and architecture. To this end the building was decorated externally with a statue of young woman emerging from the sea (by Professor Frederick Herkner (1902-1986), Professor of Sculpture at the National College of Art) inspired by a line from a W.B. Yeats’ (1865-1939) poem ‘your mother Éire is always young’. This sculpture was the result of a competition organised by the Irish Government although Scott later claimed it was he who held the competition. Internally it was decorated with a large mural by Sean Keating depicting elements of Irish life and history. There was also a large oil painting by Maurice MacGonigal who was by now the Assistant Professor of Painting at the NCA, celebrating Ireland’s contributions to America’s history and development. Keating disliked Scott – according to Ciaran MacGonigal, Keating ‘hated the sight of him’. Scott gave Keating the commission as a way of hedging his bets and gaining influence and credit with the older generation of Irish artists.

Originally ÉIRE – the Irish language version of Ireland, was to appear on the building but the Government led by Eamon de Valera decided that IRELAND was more appropriate. ÉIRE was used in the constitution but was relatively unknown outside of the country. Ireland was used even though Scott would have preferred ÉIRE as he thought that it looked better as it was almost symmetrical. Scott commissioned the English typographer Eric Gill to design the typeface. Scott also integrated colour into the pavilion. Although the building was largely white in the plaster work and glazing bars, the columns around the doorway were green, and the concrete slab surmounting them was orange thus bringing in the colours of the Irish tricolour. While Scott was not overly nationalistic, he was patriotic and proud of his nationality and heritage. It was also the lead up to the Second World War and the Irish Government would have been keen to promote itself as a sovereign state wholly unconnected to Great Britain in order to maintain its policy of neutrality – this would also have influenced the Government’s desire to have the pavilion as far from the British Empire pavilions as possible.

It was selected by an International jury as the best building in the show. As a result, Scott was presented with a silver medal for distinguished services and given honorary citizenship of the city of New York by the then Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. He also received a fee of three hundred and fifty guineas. Other better known architects who designed national pavilions for this World Fair included Alvar Aalto of Finland and Oscar Niemeyer (born 1907) of Brazil. The building was officially opened on the 13 May 1939 by Tanaiste Sean T. O’Kelly officiating in place of the Taoiseach Eamon de Valera, who could not attend because of the rapidly worsening European situation.

During the Second World War, or the ‘Emergency’ as it was called in neutral Ireland, Scott’s practice operated out of accommodation in Clare Street, Dublin. It survived on small commissions such as cinemas in Athlone and Clonmel and interiors of public bars. Building materials and money were in short supply and architects were hard hit. The artist Louis le Brocquy (born 1916) who produced work for Scott during these years wrote:

… things were not easy for Michael either, as might be expected of an inspired contemporary architect who repeatedly refused to compromise his growing vision, a revelatory vision of plastic rectitude, of pure, unsentimental, unadorned rightness.

Scott had been known to walk away from commissions that he did not find challenging or interesting. Increasingly he was passing on work and commissions that he had received to young graduate architects whose work he admired. The Ritz Cinema in Athlone (1939) is a case in point. Although attributed to Scott it was in fact designed by Bill O’Dwyer who was working and studying in the office at that time. While it is impossible for a successful architect to fully design all the buildings that come into his practice, Scott seems to have produced only rough sketches for the project leaving O’Dwyer to design the building. O’Dwyer was to be responsible for many of the cinema commissions undertaken by the firm in these years including two other Ritz cinemas at Carlow (1937) and Clonmel (1940).

The Ritz, Athlone was constructed on pilotis on a riverside site. The original perspective drawings include large areas of glazing on the façade as well as between the pilotis on the side elevation, where a riverside restaurant was to be sited. Most of this was never completed as the budget did not allow it to be fitted to the finished building. The interior was dominated by a double height public space lit by a large expanse of glass on the front façade. This can be seen as a predecessor to the entrance foyer to the Government offices in Busáras, with its fully glazed façade. Again incorporating the work of artists, the interior of the theatre had carved figures designed by Louis le Brocquy. With its large areas of white plaster, glazing, porthole windows and flat roofs, the building reflects the maritime imagery of the time, and still seems quite alien in this traditional country market town. It is clearly of the same lineage as Geragh and the World Fair Pavilion. The building today was largely intact, though much dilapidated and derelict, until it was finally demolished in the late 1990s.

Before Scott went to France, he became involved with Córas Iompair Éireann (CIE) the National Transport Company which came into being on the 1 January 1945 as a result of the Transport Act of 8 December 1944. This was the last of a series of transport amalgamations as the independent bus companies and the railway companies had joined forces into two companies – Dublin United Tramways and Great Southern Railways. The new head of this transport firm was an accountant, A.P. Reynolds. Reynolds had built up a successful small bus company, The General Bus Company before the amalgamation and was friends with Sean Lemass (1899-1971) who was the Minister of Industry and Commerce in 1945. Reynolds was supposedly a moderniser but his tendencies were more towards modernising buildings than improving CIE’s rolling stock and services. He was also a race horse owner and went racing with Michael Scott with whom he was also good friends. Scott was responsible for alterations to his house Abbeville, County Dublin, designed by James Gandon (1743-1823) and now owned by Lemass’ son-in-law Charles Haughey (born 1925).

Scott had always made a point of cultivating those in power for commissions. In Ireland in the 1930s and 1940s there was little in the way of large architectural commissions that were not provided by either the Government or the Roman Catholic Church. Unlike the firm Robinson Keefe who cultivated the church hierarchy and educational institutions, and built a large number of churches and schools in the Dublin suburban area, Scott attached himself to Government ministers. He became very friendly with Sean Lemass who would later be Taoiseach between 1959 and 1966 and Scott’s influence over the arts and architecture would be at its height at that time. In later years he was also very friendly with Charles Haughey, but Haughey was of a younger generation and friendly with Sam Stephenson (born 1933) and Arthur Gibney (born 1932) and so Scott’s influence did not extend to his practice getting the best commissions of that period.

Also a member of this circle was the Jesuit Fr. Donal O’Sullivan who was later to become head of the Arts Council and also a friend of Scott. Scott had worked for the Jesuits at the behest of O’Sullivan. In later years this close relationship of Lemass, O’Sullivan and Scott was ‘effectively state control of the arts’. So naturally enough, Scott got control of any CIE commissions that were going, being appointed Consultant Architect to CIE by Reynolds. Indeed at one time Reynolds wanted CIE to take over Scott’s practice and have Scott and his team as in-house company architects, but Scott resisted, thinking of the political interference in projects and in the hiring of staff that would be incurred.

Scott generously passed on many of the commissions to promising architects, remaining as CIE’s Consultant Architect. Scott’s role as consultant architect meant that he passed all final drawings and designs for the various projects. These other projects included a large complex of railway workshops to be built at Inchicore (this was passed on to Eoghan Buckley and John O’Gorman but was never built due to CIE’s financial problems) and the Bus Stations at Clonmel (completed by Eoghan Buckley, 1948) and Cork for which Scott sketched plans. A scheme for a large manufacturing works at Broadstone Station was passed on to Brendan O’Connor but was never executed due to a change in Government. However he kept the Dublin Bus Station and other key projects for his own practice.

The first of these was the Inchicore Chassis Works designed for the production of bus and lorry parts. The complex contained offices for administration and production as well as accommodation for manufacturing and testing. For the main factory, it was considered that a space of 330 feet by 150 feet with one central row of columns at 30 feet centres would allow a degree of flexibility in the layout of plant as needs changed. A crane bay was placed on the east side allowing the west side to be extended if the need arose. The building was very much planned around flexibility and extendibility – all to no avail in the end. Externally it was one of the most modern factories in Ireland with large areas of vertical patent glazing in the factory space and continuous steel windows from floor to ceiling for the offices. At the RIAI, it was suggested that it should be the winner of the Gold Medal for the period, but the committee led by Raymond McGrath (1903-1977) decided that, as Scott was obviously going to win it with Busáras, it should go to someone else. So Alan Hope (1907-1965) won with the Aspro factory, Naas Road, Dublin (Walker, 1995, p. 123). This of course is Scott’s story, as he then goes on to belittle the quality of Hope’s work, so this may or may not be true. As soon as the building was completed however, a debate arose on what to do with it – CIE’s financial problems would not allow them to begin producing vehicles. It was used as stores for several years and then sold on – its original function for CIE never realised. It now operates successfully as a machine workshop for an engineering firm.

The second of these buildings was Donnybrook Bus Garage – completed in 1952. This was a much more radical building than Inchicore and was designed in association with the Danish engineer Ove Arup (1895-1988) whom Scott persuaded to set up offices in Dublin (the first overseas Arup office). John Harbison who was the first engineer to work for Arup in Ireland was in fact interviewed for the job by Scott. Arup was contacted by Scott in 1944 when the prospect of the Bus Station project was first mentioned. Scott had gone to England to find a good experienced engineer as he felt that engineering in Ireland was not up to European standards of that time. He approached the Architectural Association in London who suggested that he should ask any English architects that he may know. So he contacted the architect Howard Robinson whom he met at the New York World Fair. Robinson suggested Arup, describing him as ‘rather an arty chap’ like Scott. From that point on, Ove Arup and his firm were responsible for supervising the engineering for all the buildings produced by Scott’s practice. Arup at this time was quite successful and well known after his work with Tecton on projects including the Penguin Pool and other enclosures at London Zoo (1934-1937). His practice had become known for its fresh approach to difficult structural problems and Arup himself was known for his new ideas on concrete construction.

Donnybrook Garage was carried out by some of Scott’s staff in association with another architect Jim Brennan (1912-1967), who in some journals is credited with the building although Scott’s firm is usually listed. Brennan had previously worked for Scott in the late 1930s on Portlaoise Hospital and Scott’s team on this project included Patrick Scott and Kevin Roche. Originally it was the first of a series of eight proposed garages for one hundred buses to be built to the same design around the country. It was the first building in the world to have a concrete shell roof lit by natural light from one end to the other. Each shell was poured in situ with large wooden moulds that were dismantled and moved on to form the next one. This form was suggested by Arup as a suitable approach to the design. The other seven garages were never executed and the concrete moulds were destroyed after the completion of Donnybrook due to Government politics and the advice of a senior civil servant Dan O’Donovan. O’Donovan was a man of very strong personal convictions on building and was later to be appointed to oversee the building of Busáras, to the despair of Scott.

Externally the building’s elevations are dictated by the roof form which is visible along the sides. Smaller flat roofed buildings were built next to it but do not intrude on the distinctive shape of the building. The faith that Scott showed in the ability of Arup, in allowing him to dictate the external appearance of the building through its engineering was to be repeated at Busáras. Decorative ribs are visible along the side elevations. Originally it was coloured externally in a grey and yellow paint scheme designed by Patrick Scott, which has since been painted over. Internally the garage is an imposing well-lit internal space uninterrupted by columns or internal walls.

The controversy and politics that beset these two buildings were to pale into insignificance beside the troubles that surrounded Scott’s third CIE commission. This building was the first large modern building to be built in the city of Dublin and the first major public building to be built in Europe after the Second World War. It was also to bring him acclaim and attention from the public – this was the Dublin Central Bus Station, to be known as àras Mhic Dhiarmada or Busáras. Busáras was to win Scott the Royal Institute of Architects of Ireland Triennial Gold Medal for Architecture and many accolades from architects all over the world. It was not always so. During the early construction process much controversy was circulating about the building in newspapers and journals.

By 1945, Scott had surrounded himself with a young and talented team, most of whom were recently out of college or indeed still studying. The team included Wilfrid Cantwell (born 1920), Kevin Fox (born 1922), Patrick Hamilton (born 1921), Kevin Roche (born 1922), Patrick Scott (born 1921), and Robin Walker (1924-1991). Many more worked on the project to a lesser extent. According to Sean Rothery who worked for Scott from 1951, Scott always let his team work on their own and he rarely interfered. This engendered in the young architects a sense of importance and self-belief. It was this group of architects were responsible for design of the building.

He was a bit like Diaghilev. It wasn’t so much what he did himself as the fact that he assembled a group of very talented people around him, stimulating a lot of creative thinking, which made things happen. He was more of an impresario than an architect.

Wilfrid Cantwell was the main designer of the building and was principal architect until he left Scott’s firm in 1947, at which stage the main structure and façades were already designed. The importance of Patrick Scott on the project is well known as he was responsible for the internal and external decoration, but the impact of the others is not quite so publicised. Kevin Fox was one of the main assistant architects on the project and most of the perspective drawings of the various concepts were drawn by him. He took over as principal architect after Cantwell’s departure and was responsible for most of the detailing. Kevin Roche only worked on the design for a short time but contributed to the external appearance of the finished building on the pavilion storey. Patrick Hamilton also played a very important role in the design. Apart from being responsible for many details, he ran the drawing office which he run strictly and, more than anyone, was responsible for getting the building up. Robin Walker was responsible for the design of furniture and interior fittings.

Although acclaimed as the architect of the building it now seems that Michael Scott had no design input into Busáras other than in a supervisory guiding role. It was Wilfrid Cantwell who was responsible for the main elevational treatments and plans. In 1945 when Cantwell joined the firm straight out of college, little progress was being made on the design of the building. Newspaper reports state that the City Corporation did not receive detailed drawings for a long time after initial planning permission had been granted. The architect who had responsibility for the initial sketches was Barry Quinlan and progress was slow. Cantwell is said to have “muscled his way onto the Bus Station job” within a couple of months of his joining the practice and then completely took it over. This he achieved by the constant harassment of Quinlan while he was working until he got to the stage when he just relinquished control of the job – Cantwell had an abrasive and pushy personality. The finished design that was built was Design No. 12 by Cantwell and the structure was completed by the time he left the practice in 1947 to work on his own.

Wilfrid Cantwell tells a different story. According to him, two architects Nolan and Quinlan were all ‘at sea’ on the project and it was in deep trouble. The architects had been approaching it the wrong way, and he suggested an alternative proposal which Scott liked. Quinlan and Nolan left shortly afterwards to start their own practice and Cantwell was immediately appointed principal architect. Whichever the case, what is not in doubt is that Cantwell was responsible for the way the building looks today.

According to Uinseann MacEoin, who was working in Scott’s office at this time, the pavilion restaurant was designed by Robin Walker while just out of college. Throughout these years many young architects left Scott’s practice as relations between the client and the practice soured – at some times relatively in-experienced architects were left in control of the job. Robin Walker stayed on and became a partner in the last incarnations of Scott’s firm, Michael Scott and Partners in 1958 (which later became Scott Tallon Walker in 1975). Between 1945 and 1949 Walker alternated between working for Scott and travelling abroad to work and study. He worked for Le Corbusier (1887-1966) at the Atelier in Paris and Skidmore Owings Merrill. He also studied under Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) in the United States. Although MacEoin recollects that it was Walker who was responsible for the pavilion restaurant, Patrick Scott maintains that Walker was only responsible for the furniture in the pavilion while Kevin Roche, later to work with Eero Saarinen (1910-1961) in the United States, worked on the overall design of the top floor pavilion.

So many people worked on it at some time or other – Kevin Roche did some work on the pavilion floor. At one stage he had a spire on one end on a sketch plan.

Kevin Roche himself wrote:

Wilfrid Cantwell and Kevin Fox were the primary architectural assistants working with Patrick Scott on this project. Wilfrid was the project manager and planner. Together with Patrick Scott, Kevin was probably the strongest designer involved; Fred Hilton worked in a somewhat lesser role. My contribution was minor as I was engaged in a number of other projects including the bus garages in Donnybrook.

Roche left the firm in 1948 to go to America after completing sketch plans for the pavilion and Walker detailed them. Walker was a couple of years behind the others in college and would likely have had less creative input. MacEoin would have only joined the firm several months before Roche left, so it is possible that Roche was easing Walker into the project prior to his own leaving. Of those who left the company in later years Scott always maintained that with the exception of Kevin Roche, they never rose to the same heights again as they did with Busáras.

Apart from the ones who stayed with me who did marvellous buildings, none anything much afterwards, for some curious reason. Cantwell was a very good architect, first rate when he was young. So was Kevin Fox, first rate when he was young.

This is true to the extent that Cantwell and Fox never again were responsible for a building as large, as complex or as acclaimed as Busâras through the remainder of their careers. Scott would have wished to portray himself in the best possible light and would try to suggest that he was responsible for bringing the best out in them. Wilfrid Cantwell continues to work on his own, specialising in small projects and ecclesiastical architecture, while Fox worked abroad and then went into education. Scott’s dismissal of Cantwell may also be attributed to Cantwell’s less rigid approach to modernism in later years as he felt that architects should ‘take each job as they come, and assess the best approach’ or equally to his departure because Scott would not make him an associate in the firm.

After the construction of Busáras, Scott’s firm survived with the construction of smaller projects like the Bridgefoot Street Flats for Dublin Corporation. In 1958 the firm was renamed Michael Scott and Associates, bringing on board Ronnie Tallon (born 1927) and Robin Walker as partners. From then on each major project was spearheaded either by Walker or Tallon. Then the practice began to show a more Miesian influence due to Walker and Tallon’s admiration of Mies van der Rohe, with buildings like the Carrolls Factory in Dundalk and the Radio Telefís Éireann studio complex in Dublin. With this shift in aesthetics, Busáras has been described as representing a full stop in the work of Scott’s office.

This shift in aesthetics is also due to the fact that the design team responsible for the bus station had by now broken up, and Scott had retreated from day to day involvement in the design process. Cantwell had gone out to practice on his own, before the building was completed, as had Kevin Fox. Kevin Roche had gone to the United States in 1948. Patrick Scott was to leave the practice in 1959 to paint full time. Of the team that designed the Bus Station, only Michael Scott, Patrick Hamilton and Robin Walker were still with the firm by 1960 but the architects most responsible for the outward appearance of the building were gone.

Scott’s work up to the building of Busáras is divided into two strains – the purer modernism of Geragh, Portlaoise, the World Fair Pavilion, Athlone and Clonmel cinemas and the more decorative works of Tullamore, O’Rourke’s Bakery and his interior projects. It has been said by former employees that Scott tended to design in the current fashionable style – a point that was true of his practice in later years and is true today. But through the 1930s and early 1940s, it may be that Scott’s firm was still developing a mature style.

With the New York World Fair Pavilion, Scott’s architecture moved away from the formulaic arrangement of volumes as seen in his hospitals and houses, to a more organic and externally decorative architecture. Certain characteristics can be seen through buildings which otherwise may be seen as quite disparate. Tullamore, Geragh and Arthur Shield’s house all have curved bays. His later works including the cinemas at Athlone and Carlow also share similarities with Geragh – the use of porthole windows and pilotis, and the white concrete finish. These buildings of which Portlaoise Hospital may be seen as the first, were purer attempts at the New Architecture as preached by Gropius than his earlier work. After the war, his architecture began to show more external decoration, as at Donnybrook Bus Garage with its sculptural concrete shape and decoration. The logical progression of Scott’s obsession with art and decoration as well as with his use of the modern vernacular is Busáras where decoration and a large selection of materials was used externally to relieve the starkness of the façades.

Although Scott was not personally responsible for the design of the bus station, as the principal of the firm and mastermind of the project he would have had the final decision of what design was produced. Scott had very strong views and always stood by his opinions and never relented if he could help it on matters of design. The building shares similarities with previous works by Scott’s firm: the similar use of a double height entrance foyer as in Athlone Cinema, the use of the solid endwall of the New York World Fair, the use of a sculptural concrete form like Donnybrook and the integration of art and architecture. Although Scott only produced one drawing during the design process of Busáras, verbal input and suggestions would have played a role in the design, as would previous work of the practice.

One of Scott’s merits was that he could recognise a good idea when he saw it or equally a bad one. He could come over to your drawing board, see a drawing he hadn’t seen before and immediately point out a weak part of the design. Scott was a lousy architect; his judgement was pretty good but his ideas were pretty poor. The only drawing he did on Busáras was when the city architect specified an imitation Wyatt window in the stone on the south endwall to reflect the Custom House. So Scott did the drawing and submitted it to the planning office. After planning permission, it was quietly forgotten about. Wilfrid Cantwell in interview