Peter Rice (1935-1992)

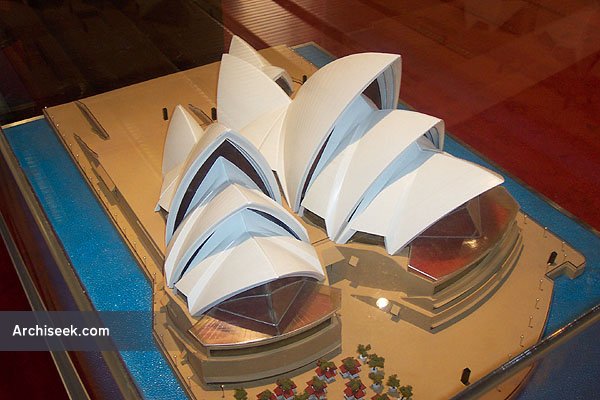

Born in Dundalk Co. Louth, Peter Rice spent most of his childhood between the town of Dundalk, and the villages of Gyles Quay and Inniskeen. He was educated at the local CBS before going to Newbridge College and then on to Queen’s University Belfast. He originally started to study Aeronautical Engineering but he found it uninteresting and switched to Civil Engineering. After he received his primary degree, he spent a year at Imperial College in London before joining Ove Arup and Partners in 1956 to work on the Sydney Opera House.

At Arups he was part of a small team which worked for three years to figure out a way to built Utzon’s shells. After three years working on the project in London, he moved to Sydney to be assistant engineer to Ian MacKenzie. After one month MacKenzie fell ill and was hospitalised, leaving Rice in total charge. At the age of 28, he was resident engineer on one of the world’s most recognisable buildings. He was responsible with a surveyor Mike Elphick for the survey and positioning of all the shell elements and tiles.

“Before Syndey I had a very primitive appreciation of architecture. Life in rural Ireland in the 1950s had given few clues to what it was all about, so I came to the experience innocently, like blotting paper ready to absorb any information which came my way.”

After the completion of the Opera House, he spent eighteen months in the United States – six months in New York and a year at Cornell where he was a visiting scholar. He returned to England in 1968 and worked with Structures 3 at Arups where the principal client was Frei Otto.

In 1971 the French government announced a competition for the centre of Paris. Structures 3 had been previously introduced to Richard Rogers by Frei Otto.

“As we sat thinking we realized that a good reason for entering competitions is not to win them but to explore relationships and design. Of course one can hope to win but, particularly when it is an open competition – there were 687 entries from Beaubourg – to set out to win is in a sense self-defeating, because it will induce a conservative and tentative approach and the principal factor will not to offend. With that in mind we approached Richard Rogers, who had just set up a joint partnership with Renzo Piano, and asked then if they would be willing to enter the competition with us. After some hesitation and indecision they decided to proceed.”

According to Rice, Piano and Rogers had a clear idea of the building and image that they wanted – an idea based on the ideas of Archigram and Cedric Price.

“It was a large loose-fit frame where anything could happen. An information machine. At its core was the belief, which had been identified in the brief, that culture should not be elitest, that culture should be like any other form of information: open to all in a friendly, classless environment. Once the architectural idea, the large open steel framework, had started to gel, our job, in one page, was to design the framework.”

“It was a large loose-fit frame where anything could happen. An information machine. At its core was the belief, which had been identified in the brief, that culture should not be elitest, that culture should be like any other form of information: open to all in a friendly, classless environment. Once the architectural idea, the large open steel framework, had started to gel, our job, in one page, was to design the framework.”

“Doing the competition was fun. It was all done quickly near the end, so there wasn’t any time for the fun to get lost. This is an important point about competitions, especially open ones. The entry was not become too deliberate or too detailed, or too closely argued a response to the brief, because the jury will only have the briefest of time with each entry. It is the idea that they will see and the spirit of the drawings.”

On 13th July 1971 they won the competition to build the Pompidou Centre. The core of the team made it to Paris that evening where they were feted by the government and the jury. Over the next few days, the remainder of the team arrived. Only Rice believed. He was the only person who believed at this stage that it could be built.

According to Bryan Appleyard’s biography of Richard Rogers “….he was the calmest man in Paris on that critical weekend. He knew that the building would be built and Sydney had taught him that you place such projects long. In this case, for example, he knew that they had to make time for themselves.”

“Peter Rice is one of those engineers who has greatly contributed to architecture, reaffirming the deep creative interconnection between humanism and science, between art and technology,” Piano once said of him. Rogers also detected “a sense of inner peace” about Rice which was reflected in everything he did.

A year later he moved to Paris. He had found it too difficult trying to monitor progress from London. Again according to Appleyard, “In this context, Rice – along with two other engineers, Lennart Grut and Tom Barker – was the best possible partner for Piano and Rogers. First, because his thinking was strategic; he clearly defined problems in all areas, not just engineering, more clearly than anyone else. Secondly, because he was sensitive to what they were trying to do; he did not, for example, try to talk them out of the 150-foot span in spite of the huge problems it created in the design of the steel trusses.”

Eventually they succeeded, and Rice moved on to other projects, working with architects such as Piano and Rogers, Norman Foster. In 1978, he was again involved in another major Rogers project – Lloyds of London. This was to be another long project being finally completed in 1984. It was beset by many delays and problems. By 1980, “the three main teams – architects, engineers, and contractors – seemed to be badly out of step. Arups in particular, were some way behind in producing the structural solutions for the design. This is said to be an occupational hazard of working with Rice, whose brilliant strategies are frequently followed by prolonged agonizing about the engineering”. But by 1981, the project was largely back on track.

During this time, he was involved in other projects notably the Fleetguard Factory at Quimper in France, and Stansted Airport in London.

In 1977 after the completion of the Pompidou Centre, he set up his own practice RPR (along with Martin Francis and Ian Ritchie) although he continued to work for Arups as a partner. This contributed to his workload and huge output. Though Rice was based in London, where he worked with Michael Hopkins on the tented Mound Stand at Lord’s, much of RFR’s work was in Paris. It included the great glass walls of the Cité des Sciences at La Villette and the tent-like canopy that softens the monumentality of the Grand Arche at La Défense.

In 1977 after the completion of the Pompidou Centre, he set up his own practice RPR (along with Martin Francis and Ian Ritchie) although he continued to work for Arups as a partner. This contributed to his workload and huge output. Though Rice was based in London, where he worked with Michael Hopkins on the tented Mound Stand at Lord’s, much of RFR’s work was in Paris. It included the great glass walls of the Cité des Sciences at La Villette and the tent-like canopy that softens the monumentality of the Grand Arche at La Défense.

In 1985 he was asked by I.M. Pei to help in his projects at the Louvre in Paris. Rice engineered the shell structures for the glass roofs that Pei wanted to cover inner courtyards turning them into internal spaces.

In 1985 he was asked by I.M. Pei to help in his projects at the Louvre in Paris. Rice engineered the shell structures for the glass roofs that Pei wanted to cover inner courtyards turning them into internal spaces.

By now he was firmly established at the forefront of engineering and was in great demand, working with architects such as Richard Rogers, I.M. Pei, Norman Foster, Ian Ritchie, Kenzo Tange, Paul Andreu, and Renzo Piano. The projects he worked on varied widely from Toronto’s Opera House by Moshe Safdie to Kansai’s International Airport, one of numerous projects with the Renzo Piano Building Workshop. Following their close collaboration over many years, the famous Italian architect, Renzo Piano, commented that: “Peter Rice made a great contribution to anchor the art of architecture to real life, real science, and real modernity.”

In 1992 he was awarded the RIBA Gold Medal for Architecture, the second engineer to receive it (after Ove Arup and Renzo Piano), and the second Irishman after Michael Scott. The Royal Gold Medal for the promotion of architecture was inaugurated by Queen Victoria in 1848 and is conferred by the Sovereign annually on a distinguished architect or person “whose work has promoted, either directly or indirectly, the advancement of architecture.” In late 1991, he was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He died on 25 October 1992 aged fifty-seven.