Random Building

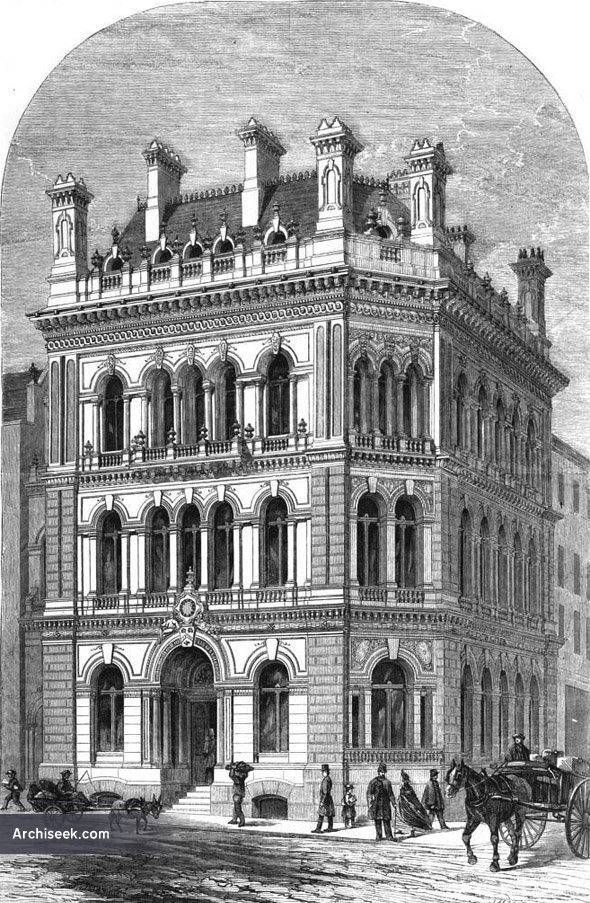

1863 – National Provident Institution, Gracechurch St., London

“We present in this number an engraving of the new offices of this Institution, at the corner of Gracechurch Street and Eastcheap, just completed under the charge of Professor Kerr, and of which occupation was entered upon within the last three weeks.

To speak of the history of the institution itself is not required of us ; but it cannot fail to be interesting to every person who sympathises with the philanthropy of our age and country to note that the ” Friendly Society” which has now erected for its business a building of this magnitude and pretension, was established little more than five-and-twenty years ago, in a second-floor room in Nicholas-lane, with very humble accompaniments indeed. The institution, in a word, is a life assurance office on the principle of absolute mutuality. We believe it never required one shilling of subscribed capital from the first; and its income at the present moment is said to reach 35O.0OOJ. a year; the value of securities in its strong-room being proportionately large.

The edifice now completed has been in progress for the somewhat lengthened period, now-a-days, of two years. The late strike of masons fell with its full weight upon the undertaking; but all’s well that ends well. The general contract has been carried out by Mr. Myers; Mr. Grissell, Mr. Shaw, and Mr. Barrett have severally been connected with the ironwork; Mr. Stewart has been decorator; and the name of Mr. Ruddock deserves mention in connexion with carving-work, and, indeed, sculptural art of great skill. The whole of the works seem to merit approbation for substantiality. Upon the good principle of giving credit to the hand as well as the head, we are authorized to say that much of the success of the work is due to the care and good craftsmanship of the foreman, Mr. Shillito.

There are five stories in the building, namely, the basement, for muniments, &c.; the groundfloor, public office; other offices on the first-floor; a second-floor to be let off; and above this the messengers’ rooms. The basement contains a large deed-room, solicitors’ examination-room, and accommodation for books, papers, and stationery, all arranged in order, as also the lavatory, for the clerks. Light and air have been provided for throughout; and in particular the deed-room has been contrived for dryness, not by iron or lead lining and gas-burners (an excellent expedient for the express creation of damp), but by the simple measure of providing the ordinary means of warming and ventilation,””a door and window to be opened at pleasure, a fire to be lighted when required, and a few common air-flues. The slate fittings for papers are remarkably complete throughout the basement generally. The access is from the public office by a continuation of the principal stair. As for the ground-floor, it is merely one large open expanse, more than 50 feet square, the whole of the division walls above being supported on about half a dozen iron columns. Here Messrs. Sinee have fitted up a complete and elegant series of mahogany counters and desks, on either side of the central line which passes from the entrance-door in front to the staircase immediately opposite, at the back. On the flrstfloor this staircase lands in a spacious central vestibule. The board-room occupies the front over the entrance, the medical officers’ looms adjoin at the corner, and tho secretary’s and chairman’s rooms look on Eastcheap, all entered, of course, from the vestibule. Here there are also several waiting-rooms. The second-floor has a separate entrance at the extremity of the Gracechurch-street facade, with a separate entrance at the back. It has been already said this story will be let as chambers. The uppermost story has also its special entrance at the extremity of the Eastcheap facade, and its separate stair; the rooms being appropiated chiefly for the residence of the messenger. The three staircases are grouped in contact at the back part of the site, and the architect has arranged them for intercommunication (both present and prospective) and no less for perfect separation’, with much care. It thus appears that simplicity of plan has been the great object internally; and accordingly it is found by visitors that the inspection of the arrangements is a thing of a very few minutes.

The exterior design will explain itself, but it is sufficiently peculiar to warrant us in requesting the architect to explain his views, which he does thus :””Being firmly attached to the classical party, he holds that classic architecture alone is calculated to give lasting satisfaction in a London commercial building. At the same time he sees no reason why the spirit of the picturesque should not be openly acknowledged. Once more he suggests that modern English taste will be found to favour permanently in decorative art only such forms as shall be delicate and graceful in detail rather than bold and heavy,””playful rather than severe; certainly simple rather than complex. The so-called Italian model of general design is adopted, with its simple horizontal lines; simple symmetries, simple arithmetical proportions. Uninterrupted arcuation throughout, recessed porch and balconies, a special treatment of the splayed angle, a high-pitched roof, undisguised chimneys and dormers, and some lesser features of similar tendency, supply the picturesque element. Mouldings of a Greek type, carvings in every case simple, and comparatively flat, decoration concentrated, and features generally small, give a delicate character to the whole, which is equivalent in effect to elaborate ornament, without suggesting that ostentation which the English mind always desires to avoid.

What may be called the focus of the effect is the entrance porch. The key-stone of its wide outer arch is the shield of the institution : this carries a carved stone clock-case, surmounted by a vase, j and supported by a pair of well sculptured figures in full relief, being the heraldic supporters of the institution,””Justice as a woman (whether this is not Charity, however, or some other female virtue, is doubtful), and Strength as a lion. Heralds say the head of the lion should be next the shield, but we will let the architect have his own way. The sides of the archway are formed with three pairs of red granite shafts with foliated capitals, and the successive soffits, together with the semicircular panel above the door, are delicately carved in flat water-leaves and shells, the depth of the recess being in all 5 or 6 feet. The windows have massive mahogany casements throughout; the entrance doors are of the same, with very nicely carved spandrils; and around a massively moulded mahogany door-frame there is a lining of white marble, which forms a delicate finish. A very little gilding is introduced in the porch.

The stone is Portland; the roof is covered with green Westmoreland slates; a slight iron cresting, still of Greek character, runs along the ridges; the glazing, it need scarcely be said, is of British plate, in single squares. The floors are Barrett’s fire-proof.

The endeavour after novelty of design is not confined to the exterior; and the iron-work of the ground-floor especially is carefully studied, with the object of producing a highly ornamental effect without resorting to sham in any way. The columns, of cast-iron, have delicately-foliated capitals, carved brackets, enriched base mouldings, and so on, all of iron fitted on the plain casting.

The girders are the every-day box girders, of rolled iron, but no less ornamental. The sides are filled in with cast-iron panels, perforated in a pattern, fastened to the top and bottom flanges and the boxes over the columns covered with well carved medallion plates, all in symmetrial lengths. The rivet-heads on the soffit are also covered with cast-iron pateras, screwed on. The iron-work is thus, at little cost, rendered the most ornamental feature in the interior, and its effect of lightness is universally remarked upon.

Credit is due also to the architect and Mr. Stewart for their having taken considerable pains in making the experiment whether colour decoration may not be introduced into places of City business. The attempt is one that requires more than ordinary discretion; but when we bear in mind that the National Provident Institution is largely identified with the “Friends,” that the decorator himself is a member of that most respectable and unimpassioned body, and that the architect in this case has frequently stood up as a champion of the little-colour-if-any school, we may be satisfied that as little colour as possible has been here ventured upon. It is enough for us to point out that the attempt has been fairly made, and to say that we believe ” City men,” who must be the judges, do not disapprove.

As regards that satisfaction of the client which every architect considers to be his boast when unreservedly accorded, it must be a satisfaction to Mr. Kerr to know that at the annual general meeting of the Institution, held on the 22nd of December, when there were assembled a large number of that British public which always claims full license to be allowed to differ, there seemed to be no difference upon the approbation of the building. For our own part, we point to it with very great pleasure as one of the most successful works of its class in the city of London.” As published in The Builder, January 3, 1863.