1857 – Trinity College Museum, Dublin

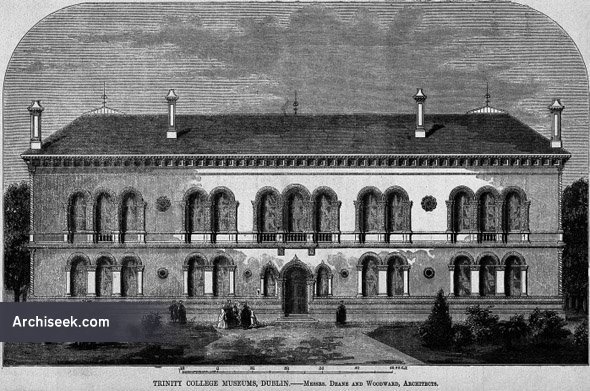

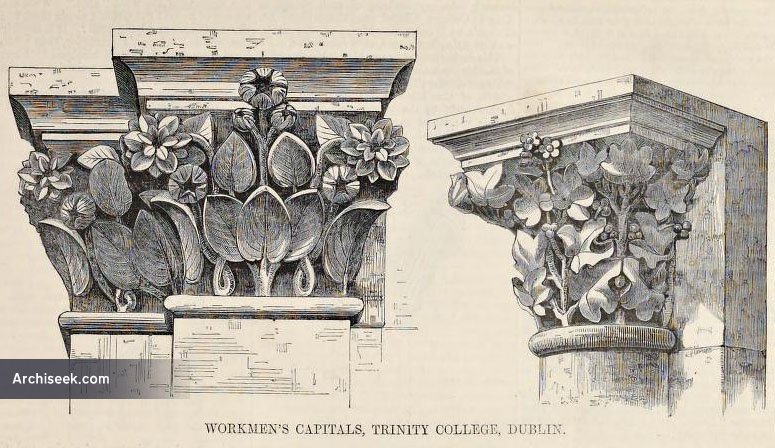

The winning design of a competition to design a museum and lecture hall complex for Trinity in 1852, this is one of the first statements in architecture of pre-Raphaelite ideals. A palazzo style structure with Lombardo-Romanesque detailing, the museum is highly decorated with over 180 different carved capitals. The most impressive part of the building interior is the hallway and staircases.

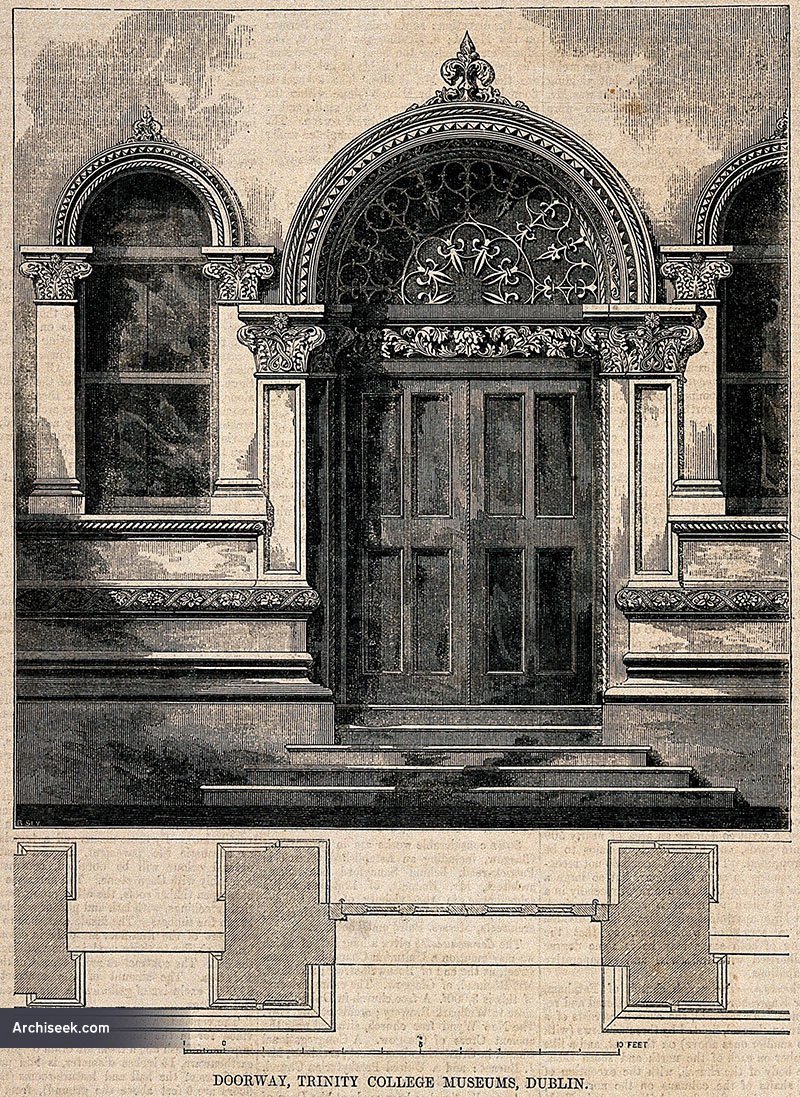

The exterior is richly decorated and although pretty dirty after years of Dublin pollution, the detailing around the windows and doorways is still impressive.

The columned hallway leads into a double domed chamber with a splitting staircase leading into two byzantine arcades. At one stage there was a plan to have the interior decorated with frescos by Rossetti. Many of the interiors designed for the building by Deane and Woodward were never executed due to the College resident architect John McCurdy persuading the Board of Trinity otherwise. This means that many of the interiors are poor attempts by McCurdy.

Deane and Woodward went on to redesign the College Library by Thomas Burgh by replacing the original flat roof with a great romanesque barrel vault and mansard roof.

From The Book of Trinity College Dublin 1591-1891 “The modern Venetian Palace in which the Engineering School of the College is so nobly lodged—a building which called forth the hearty commendation of Mr. Ruskin—was designed by the firm of Sir Thomas Deane, Son & Woodward, who subsequently were the architects of the University Museum at Oxford. The contractors were Gilbert Cockburn & Son. The building was erected in 1854-5, at a cost of £26,000. The carving of the capitals and other stone-work was done by two Cork workmen of the name of O’Shea, who were afterwards employed by the architects in the elaborate carvings executed for the Oxford Museum. The style has been described as Byzantine Renaissance of a Venetian type; but the building is in truth a highly original and beautiful conception worked out into a harmonious and satisfactory whole. The base is, critically considered, perhaps the best part. The exterior may suggest Venice, and the interior certainly suggests Cordova; and yet there is nothing incongruous with the very different surroundings, nor is there in the work any of that patchiness so often apparent in adaptations of foreign styles. It is something in itself complete, dignified, and appropriate. The general dimensions are—length, 160ft.; width, 91ft.; height, 49ft. to the eaves. The building is faced with granite ashlar, with Portland stone dressings elaborately carved. The building, as is shown in the accompanying drawing of the southern façade, looking on the College Park, is of two stories, with a broad and richly carved string course marking the division. The round-headed windows are disposed most effectively in groups: in the façade there is a group of four in the centre, one on either side, and a group of three at either end; in the east and west fronts there is[222] a group of three in the centre, and one on either side. The arches of all these spring from square pilasters carved in florid style in Portland stone, and under the windows of the upper story are low balustrades. Between the groups of windows in either façade are discs of coloured marble let into the masonry, and with a circular bordure of carved Portland stone and smaller pieces of marble; the whole harmonising with the windows and forming a most effective ornament—simple, original, and interesting. At each corner of the building are scroll pilasters of great beauty. The roof is low pitched, and an Italian cantilever cornice forms the eaves.

The accompanying illustration represents the main doorway opening on to the New Square, and looking to the north. Within the building is a spacious Hall lined with Bath stone ashlar, with low marble pillars and rich stone capitals, twenty-four in number, disposed at different levels, and supporting Moorish arches; the whole suggestive, at least, of the architecture of Moslem Spain. The first floor is reached by a broad staircase of Portland stone, with a handrail. Irish marble is used in the pillars and Irish Serpentine in the handrail of the staircase. Two pillars of Penzance Serpentine are the only pieces of marble not of Irish production.[163] The whole is lighted by two low pendentive domes constructed of coloured enamelled bricks, arranged in geometric patterns, and singularly light and free in construction. The height from the floor is 46ft. 6in. The illustration on next page shows the Hall and Staircase looking east. Half-way up the staircase, facing the main entrance, is the clock in magnetic connection with the Observatory at Dunsink. It is a Regulator, fitted with an electro-magnetic pendulum; and was put up in March 1878. An electric current is sent out automatically every second by the standard clock at Dunsink Observatory.[224] This current goes first through and controls the clock which releases the Time Ball at the Port and Docks Offices, then through the public clock in front of that office, and on to the standard clock in Trinity College. From this clock the current is sent out through the two timepieces over the Entrance Gate within and without the College, and then on to the Royal Dublin Society, where it controls the clock in the Entrance Hall. The Time Ball at the Port and Docks Office is furnished with an electrical arrangement, designed by Sir Robert Ball,[164] which automatically signals at Dunsink the moment the Time Ball falls, so that any error in time is immediately known to the person in charge. All the electrical arrangements were made and fitted up by Messrs. Yeates & Son of Grafton Street.”