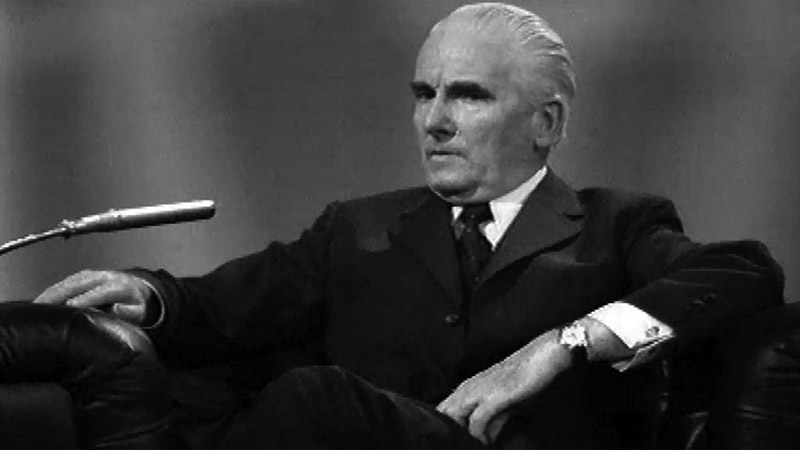

Interview with James White on Michael Scott

James White (16 September 1913 – 2 June 2003) worked as an art critic in Ireland from the 1930s and was the curator of the Dublin Municipal Gallery from 1960-1964. He joined the National Gallery of Ireland in 1964 and became Director in 1968, a post he held until his retirement in 1980. He also served on the Arts Council in the 1960s with Michael Scott for many years. Interviewed 1 April 1996.

Not being an architect nor having any training in architecture, my contact with Michael Scott was purely social and one of my closest friends was also a close friend of his, Louis Le Brocquy and a couple of times when we were abroad, the time when Le Brocquy won the Biennale in Venice, I went over and Michael Scott came out as well you know. He was always a good socialiser, he doesn’t in fact stand strong in my memory with what you might call any particular kinds of views. He followed the line of modern art, modern painters, modern sculpture and of course modern architecture. And I don’t think he had any other leanings in the art world apart from modernism, to the best of my knowledge. I knew him of course for many years and I never heard him actually moving into other areas other than purely modern Irish art forms and a few well known modern painters of the day. Of course the whole movement of the Dutch painters who introduced cubist abstract sculpture and architecture and Mondrian he liked. Mondrian, he would have been particularly keen on.

I had once a rare experience actually in that area. A very close friend of mine was a Swiss art critic called Carola Giedion. I mention her name because her husband was a famous architectural historian who wrote a book called Time, Space, and Architecture. His name was Sigfried Giedion and she was an art critic in Switzerland and I stayed with her in Zurich where she lived. When she heard my name, when I first met her in Paris in the late 30s, when she heard my name was James she said you must know about James Joyce. I said I do know some things, she said that James Joyce was her great friend. When he lived in Zurich he lived very close to me, I was with him when he died and I had a face mask made of him after his death. Some years after that she came to stay with me in Dublin and she wrote to me and said she was going to bring this mask of Joyce with her to Dublin and she wanted it put in its proper place. So I said to her, look I think Michael Scott whom I know is doing a new Abbey Theatre as it had burnt down. I said it might be worth considering giving that to the Abbey Theatre and it could be exhibited in the new Abbey Theatre which was a good source of background for James Joyce, at the time there was not a Joyce Museum out in Dun Laoghaire where there is now. So she decided she’d do that and so that I introduced her to Michael Scott.

And she gave him the death mask, it was to be cast in bronze for the Abbey theatre and in due course it was placed in the Abbey Theatre. A good many years later, perhaps about ten years ago, it was put up for sale in an auction in Dublin, I think in Christies. it was the original death mask and I got a phone call from Stanislaus Joyce, James Joyce’s grandson asking me what the hell I was doing allowing Carola Giedion’s death mask to be sold for auction in Christies. So I got on to Michael Scott and eventually he withdrew it from the auction. What he actually did was, when he had the death mask made, the original bronze cast, he also had copies of it made. The original was the thing that Stanislaus was on about, see he was going to sell that. I think the suggested selling price was around £16,000.

Its now in the James Joyce Museum out near Scott’s house. I don’t know if you’ve been out in the house, I don’t know who’s living there now. His daughter Ciaran who’s working in film, I think probably inherited the house.

He liked to be against the public, he liked to be flaunting public opinion and he was the source of a lot of agitation especially on architecture but generally he was well liked. He was very, I wouldn’t say gay because he wasn’t, he enjoyed drinking, playing around and having fun. His wife was difficult, an extremely difficult woman. She came on that trip to Venice with us and she caused ructions. She was always slow and lagging behind, I remember taking her by the arm because she was lagging behind. She wasn’t very strong, she drank too much as well. But in general that was one of my particular memories of Michael is that instance of the death mask of James Joyce. I think you’ll find lot of references to it in the press of the time.

I think I was probably Chairman of the Arts Council when he was on it, I’m not sure but there is a book on the arts council by Brian Kennedy of the National Gallery. he wrote a book on me once also. Its quite an interesting book, and he lists all the dates of all the people involved. While I was on the Arts Council we had a certain incident which became something of a scandal in a sense. Fr. Donal O’Sullivan was chairman of the council. He was a Jesuit and was very much way out in the modern art scene with Michael Scott. And there was a group of them who tended to buy pictures in the Taylor Gallery, it was originally the Dawson Gallery. The Dawson Gallery was in Dawson Street, Leo Smith ran it and all the artists who exhibited there tended to be bought by the Arts Council for its collection. The background to that, was they drank as a crowd together, they drank quite a lot and Leo smith used to keep plenty of whiskey and he’d pour O’Sullivan and Michael Scott lots of drinks. He made quite a lot of money. The newspapers of the day made quite a thing of it. That kind of thing happens a lot on boards like art councils you know when you get a group of individuals and their views are in agreement and in control. And not so much in control but to overwhelm the others and people who hold contrary views and in consultation get themselves talked down. This group was O’Sullivan, Michael Scott and Bobs Figgis and they lined up to back these modernists. I was sometimes backing the artists themselves, artists like Louis le Brocquy and Pat Scott, but they went too far with it and I think I was brought in to do a job on the council to make it a little more open to other influences and tastes. Donal O’Sullivan was the rector of the Jesuit College down in Tullybeg and they patronised Evie Hone in a big way, I’m a great fan of Evie Hone myself. I used to review all her works and I was the principal publiciser of Evie Hone. Because O’Sullivan had taken over in Tullybeg and continued to support her, he was identified with this aspect of cubist art, kind of out of Cezanne, if you know what I mean.

That was caused by the interest in the Living Artists, the Irish Exhibition of Living Art which was originally started by Evie Hone and Mainie Jellet and it was set up in opposition to the RHA exhibition. They got the same place the National College of Art exhibition space through pull and it became the new modern anti-academic thing and Michael Scott, Fr. O’Sullivan, Norah McGuinness, Fr. Jack Hanlon were involved in that group of artists together. What they were concerned about was the right of the moderns to be exposed to the public. That was a very large part of Michael Scott’s activities to the side. If you look at Dublin in the 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, and 70s Ireland was gradually moving forward into modern things away from the academic traditions. Until 1943 when the Irish exhibition of living art was founded, the only official art was the RHA’s annual exhibition held every year in May. It was the big exhibition of the year and all the ladies would be dressed up to have their pictures taken for the papers, you know the sort of thing.

In those day there was one art gallery in Dublin. You cant believe the changes. When I started as an art critic in the 30s, there was one art gallery and that was Victor Waddington’s in South Anne Street and now I’d say there is about a hundred galleries in Dublin and all over Ireland there are amateur societies and painters exhibiting in galleries elsewhere and on the railings of Saint Stephen’s Green and Merrion Square and elsewhere. Ireland is full of people painting, there was nobody painting in the years I’m talking about. It’s gradual change that developed in my time in this way that brought us out of a very, very conservative Ireland and into the present situation. Nobody in Government ever paid any attention to art, talked about, looked at or even went to art exhibitions – no interest, they were coming from a different background. So it was a gradual movement of influential and intellectual figures into this modern art thing and there was great publicity from London and Paris etceteras. So there was a spreading outwards. Michael Scott was very influential in this.

He would have come at it largely through the interest of Mondrian and through the school of painting in Holland. Their pictures with the rectangles and lines was very architectural, they look very like an architectural plan and this would have appealed to Scott. Architecture was moving away from the old styles of architecture with the use of new materials and techniques. This whole modern Dutch art is really very close to modern architecture. The growth of architecture and artistic form will always to some extent be linked together.

I knew Laurence Campbell slightly. He was not really as an artist, not really much attached to the modernist idiom, he was direct. He was an interesting and good sculpture but not in any way identifiable with the modern movement. Maurice MacGonigal was really a very attractive west of Ireland painter but didn’t have much artistic connection with Scott. Patrick Scott always done mostly abstract painting. He was actually more interested in what I would call touch paintings, much more interested in landscape and the suggestions of clouds and things with tiny dots of colour. He was always abstract, toying with the abstract and abstracting what was in front of him.